Mohamed Ali Eltaher: When the Tunisian Destiny Met with the Palestinian Cause

Adnen el Ghali

We commissioned this historical text for this edition of the ZAT. The author sends his sincerest gratitude to Hassan & Mouna Eltaher as well as Walid Maaouia, who generously shared their family archives and allowed him to collect their precious testimonies. English translation by Mary Sarsam and Noureddine Fekir.

Mohamed Ali Eltaher with Habib Bourguiba and the First Lady during his last visit to Tunisia in 1966

It was in his capacity as “a great fighter in the Arab world, a renowned journalist, and a personal friend of President Bourguiba”1 that Mohamed Ali Eltaher was welcomed at the Aouina airfield in June 1958 by a large regimental band. Much more than Arab or Maghreb unity, this man, as brilliant as he was eloquent, embodied in Tunisia a longstanding commitment to Palestine and the inalienable rights of its inhabitants.

Born in Nablus in 1896, his father, Aref Eltaher, enrolled him in a kuttab (Koranic school of elementary education) in Jaffa, where he spent his youth. While his early education is not widely known, his work as a journalist was a testament to his talent and his popularity in both the literary and political fields.2 After only a few years of activism, he became the Jaffa correspondent for the Beirut-based Lebanese daily Fata al-ʿArab. In 1914, at the age of 18, he published a groundbreaking article titled “The Zionists in Palestine,”3 warning of the dangers of Zionism.

Portrait of Mohamed Ali Eltaher. Beirut, 1974

The First World War and its disastrous consequences in the Levant forced him to move to Egypt, where his political activities angered the British authorities, who imprisoned him from 1915-1917. Mohamed Ali Eltaher returned to Palestine at the end of the war. He devoted all his time to Suriya al-Janubiyya, the newspaper he had founded in Al Qods (Jerusalem), of which he was the editor-in-chief. Although he was appointed to work in the Post and Telegraph Office, he resigned and left Palestine. At the time, Palestine was under the British mandate, a move that was intended to endorse the Zionist project.4 Thanks to the training he had received in the olive trade in Nablus, he was able to live on the income from his modest shop in the Sayidina al-Hussein district of Cairo. Within a few years, the store had become an important political meeting place for representatives of the Arab and Muslim worlds. Eltaher went on to found the Palestinian Arab Information Office in Cairo and the Palestinian Committee, which helped journalists, writers, poets, and lawyers to meet and engage in a mission to inform the Arab and Muslim nations about the struggle initiated by the Palestinian national movement. The local press, especially Al-Liwaaʾ al-Masri, allowed him to write in its columns, which helped him to resume his task of making people aware of the dangers of Zionism and the creation of a Jewish state aided by the British. In 1924, Eltaher decided to found his own press organ, Al-Shura, which was initially designed to deal with oriental affairs (Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan) and whose prerogatives he extended to the defense of Arab causes and the liberation of oppressed peoples wherever they were. The newspaper's headquarters became an important political circle where the Tunisian Abdelaziz Al Thaalibi5 rubbed shoulders with the Moroccan Allal Al Fassi, the Syrian Chokri Bey Al-Kouatli, and Arab nationalist and pan-Islamist figures from around the world.

After he visited Palestine in 1925, he became more virulent and critical. It did not take long for him to incur the wrath of the colonial powers, especially Great Britain, which banned his publications and confiscated them. He benefited from a great wave of solidarity from his Arab colleagues, who allowed him to publish free of charge and in complete freedom in the columns of the newspapers Al-Nas, Al-Minhaj, Al-Jadid, Al-Shabab, and Al-ʿAlam newspapers.

Mohamed Ali Eltaher with Habib Bourguiba and the First Lady during his last visit to Tunisia in 1966

Like thousands of Palestinians—Muslims and Christians—all his requests for a Palestinian passport were denied by the Mandatory Power, which nevertheless generously distributed them to the numerous migrants coming from all over Europe. Increasingly harassed by the British services in Egypt, he frequently changed his residence and identity with the complicity of Egyptian officials acting on the orders of King Farouk. The coming to power of Mustafa al-Nahhas Pasha in 1942 protected him for a time from British vindictiveness.

The foundation of the Arab League in Cairo in 1944 made it possible to coordinate the external actions of the six founding powers in favor of the Palestinian cause. Tunisia and the Maghreb were also involved. Habib Bourguiba created the Néo-Destour office in Cairo and entrusted its operations to Habib Thameur and Hassine Triki, who were joined by Rachid Driss, Taïeb Slim, and Hédi Saïdi. In 1947, after the North African Congress of February 15-22, the Arab League agreed to put the Maghreb issue on its agenda. The office then became the rallying point for the Maghreb community in Cairo and was transformed into the Arab Maghreb Office6—known by Maghreb nationalists as “10 Downing Street”7. Muhammad Al-Khidr Husayn, an Egyptian sheikh of Tunisian origin (naturalized in 1932) who would become the Grand Imâm of Al-Azhar in 1952, was among those present.8

Mohamed Ali Eltaher, Habib Bourguiba and Allel el Fassi

The Palestinian cause was perceived as the mother of all causes, and the movements revolving around it called for the self-determination of peoples who were victims of colonization and dispossession. While Eltaher had been writing about Tunisia in Egyptian newspapers since the early 1920s, his meeting with Bourguiba did not take place until the following decade, an event that the Tunisian president would often mention in his public speeches. It was in this burgeoning atmosphere that Mohamed Ali Eltaher found himself at the center of an intense exchange with several Tunisian personalities who were visiting Cairo one after the other, including Habib Bourguiba. They shared a common plight and linked the liberation of Palestine to Tunisian independence. In 1945, the headquarters of the Destourian cell in Cairo hosted Habib Bourguiba, Habib Thameur, Allal El-Fassi, founder and leader of the Moroccan Istiqlal Party, and Amin El-Husseini, Mufti of Palestine, as well as Mohamed Ali Eltaher. In 1947, Mohieddine Klibi, in exile in Damascus, joined Habib Bourguiba, Habib Thameur, and Mohamed Ali Eltaher in welcoming Emir Abdelkrim El-Khattabi, Emir Fadl, Sultan of Lahj, and Allal El-Fassi.

The coup d'État of the "Free Officers" resulted in close monitoring of the free press. In 1953, Eltaher was banned from publishing his magazine, but the following year, a large number of meetings were held. In the offices of his newspaper, which could no longer be issued, he received many Arab and Tunisian personalities, including Sheikh Chedly Ennaifar and Ali Belhouane.

What followed was an invigorating stay in Tunisia, which had finally become independent in 1956. He was welcomed at the Aouina Aerodrome by a guard of honor, a privilege reserved for high-ranking personalities and heads of state. At the Palace of the Grand Viziers in Carthage, he was received by Habib Bourguiba, Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and Defense, and was granted an audience by King Mohamed Lamine Pasha Bey, who decorated him with the insignia of the Grand Cordon of Nichan al Iftikhar in the presence of Bourguiba.

Extract from Mohamed Ali Eltaher, Khamsûna 'âman fî al Qadhâyâ al 'Arabiyya, Muassasat Dâr al Rayhânî, Beirut, 1974

Palestine and the future of the Arab world were at the heart of his stay in Tunisia, where he had several meetings with leading Arab diplomats, such as Ali Noureddine Fekini, Ambassador of the United Kingdom of Libya in Tunisia, Arab scholars, such as the Algerian Sheikh Mohamed Thamini, and leading politicians, including the patrician Ahmed Zaouche, governor-mayor of Tunis, Mohamed Chenik, former grand vizier and Abdelkader Klibi, son of Sheikh Mohieddine, who had died in Damascus two years earlier.9 Mouldi Zlila, president of the Association of Tunisian Volunteer Veterans of the Palestine War, organized a reception in his honor, where Eltaher met with members of the association.

Upon his return to Cairo, he discovered an Egypt that was very different from the one he had known. He left for Damascus in April 1957. He did not know that he would never see his adoptive homeland again, nor his faithful friend El Nahhas Pasha. He left the Syrian capital and it was in Beirut that he would continue his fight for the liberation of Palestine. His apartment served as the headquarters of two important political salons, Al-Acadimiyya (the Academy) and Al-Nadwa (the Forum), where personalities from the Arab world met. Tunisians were present as well. Ahmed Ben Arafa, the Tunisian ambassador, and Ridha Maaouia, the embassy's press advisor, were among those in attendance. In 1966, he accompanied President Bourguiba on political tours in Tunisia, notably to Sousse and Monastir. Tunisia, now a republic, had transitioned to socialism under the rule of Ahmed Ben Salah. During this short stay, he was invited to the first receptions organized at the newly inaugurated Carthage Palace. This last trip to Tunisia allowed him to visit schools and public institutions, and he also paid a visit to Béja.

In the early morning hours of August 22, 1974, Mohamed Ali Eltaher passed away peacefully, surrounded by his family. His funeral procession was escorted through the streets of Beirut by a detachment of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in the presence of representatives of King Hassan II of Morocco, President Bourguiba of Tunisia, and PLO leader Yasser Arafat. The man who rests in Beirut's Martyrs' Cemetery has represented the close bond that unites Palestine and Tunisia for more than fifty years.

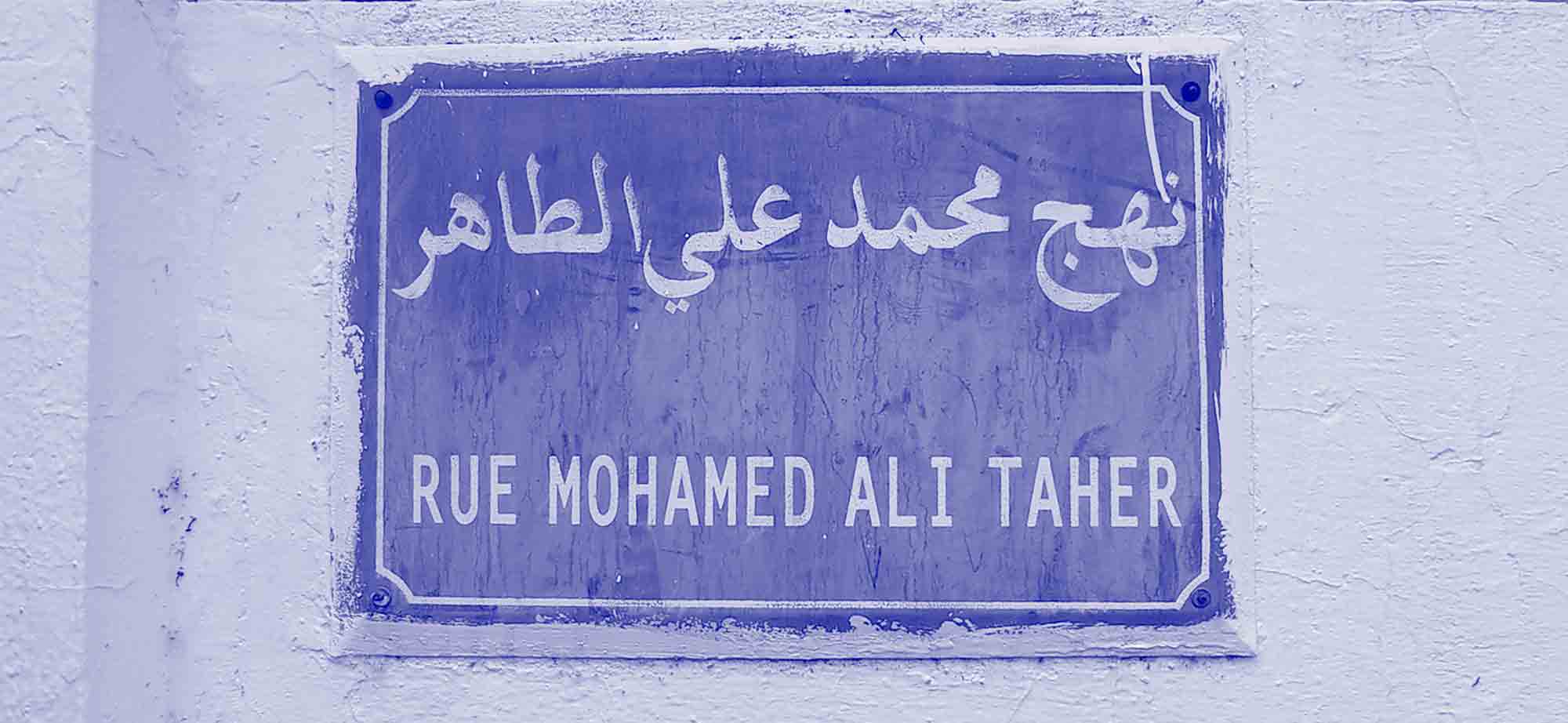

Rue Mohamed Ali Eltaher in Mutuelleville, Tunis district

1 Article from La Presse de Tunisie dated June 5, 1958 covering the welcome reserved for Mohamed Ali Eltaher on his arrival in Tunis the previous day.

2 Mahdi Abdul Hadi (ed.), Palestinian Personalities: A Biographic Dictionary. 2nd ed., revised and updated, Jerusalem, Passia Publication, 2006.

3 See his biography on eltaher.org.

5 Ṣāliḥ el Kharfī, Abd al-‘Azīz al-Tha‘ālibī, min āthārihi wa-akhbārihi fī al-Mashriq wa-al-Maghrib, khamsūn ṣūrah wa-wathīqah tārīkhīyah, Beyrouth, Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, 1995.

6 Khalifa Chater recalls the first attempt to create such a group, which took place during their exile in Berlin in the final years of the Second World War, when "amidst an occasional gathering of Algerian workers and Tunisian refugees, Neo-Destour leaders announced the opening of the Bureau du Maghreb Arabe on July 21, 1943". Read Khalifa Chater, "Pensée en exil et décolonisation : le cas maghrébin", Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 82 | 2011, 107-114.

7 Oral communication by Hassine Triki during an exchange with the author in Buenos Aires, April 2005. The office was located at 10 rue du Mausolée de Saad Zaghloul.8 Samya El Mechat, « L'improbable « Nation arabe ». La Ligue des États arabes et l'indépendance du Maghreb (1945-1956) », Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire, vol. no 82, no. 2, 2004, pp. 57-68.

Share

Read more

-

Cynicism and Western Lack of Insight Pave the Way for the AbyssSophie Bessis

-

Tunis your...Milène Tournier

-

Khalil Rabah: Art as Radical InstitutionalismChiara de Cesari

-

The Wretched of the BordersLéonard Sompairac

-

A Letter to President Macron: Reparations Before RestitutionManthia Diawara

-

Looking for AïdaJalila Baccar