Khalil Rabah: Art as Radical Institutionalism

Chiara de Cesari

Khalil Rabah presented Olive Gathering, a Tunis-specific adaptation of The Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind, at Dream City 2023. This essay appears originally in Khalil Rabah: Falling Forward / Works (1995—2025), published by Sharjah Art Foundation and Hatje Cantz in 2023. This excerpt of the piece is reprinted with the permission of the publisher and author.

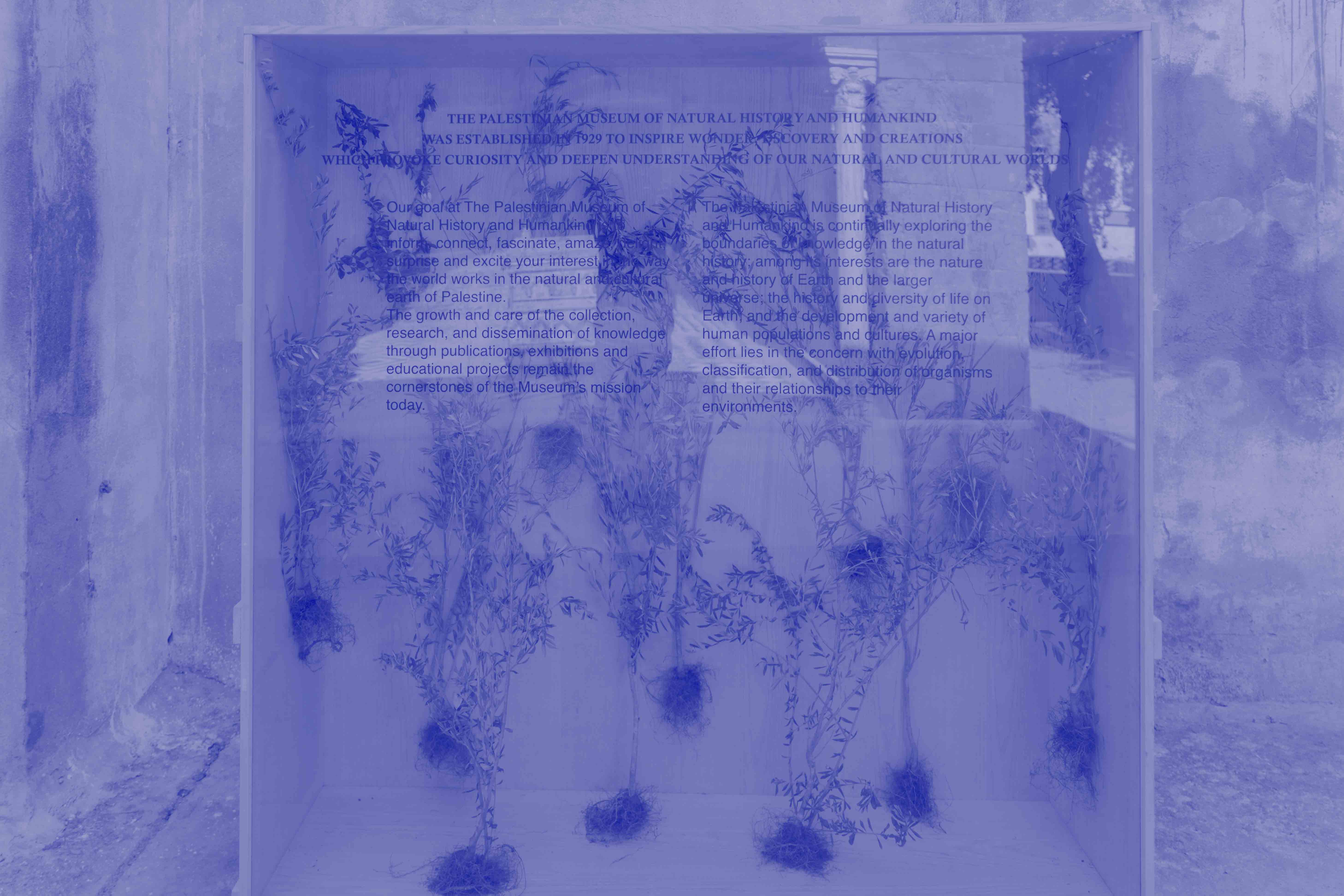

"About the Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind" from Khalil Rabah's Olive Gathering at Dream City 2023. © Malek Abderrahman.

"About the Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind" from Khalil Rabah's Olive Gathering at Dream City 2023. © Malek Abderrahman.A disjointed, dislocated relationship between reality and the image has always struck me as crucial and productive qualities of The Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind (2003–ongoing) and the Riwaq Biennale (2005–ongoing), two key works, or rather projects, by Khalil Rabah. In what follows, I will argue that both of them deconstruct the dichotomy between the real and the imaginary in order to harness the latter to transform the former. They engage with the real, pressing forward questions of institutions and institution-building under conditions of colonialism, oppression and statelessness. Both perform as cultural institutions: a national museum, in the case of the PMNHH, and, in the case of the Riwaq Biennale, a biennial and national archive. Experimenting with a set of tactics, the artist applies mimicry, mockery, displacement, iteration, anticipation, incompleteness to traditional institutional formats, whereby a logic of subversive iteration and anticipatory temporality enable the artwork to become real or partly real. Rabah’s artistic practice is arguably at the forefront of a Palestinian cultural movement that is deeply concerned with the question of the institution (What viable and emancipatory institutions should be built for Palestine?) and the overall failure of the Oslo so-called ‘peace process’ to resolve the Palestine question. More specifically, it engages with the failure of state-building by the Palestinian Authority (PA), which is itself a product of the Oslo process. The artist as archivist1 thus becomes the insti-tutor/instituting agency here, mobilising art as platform to reflect on and experiment with institutions after the failure of politics.

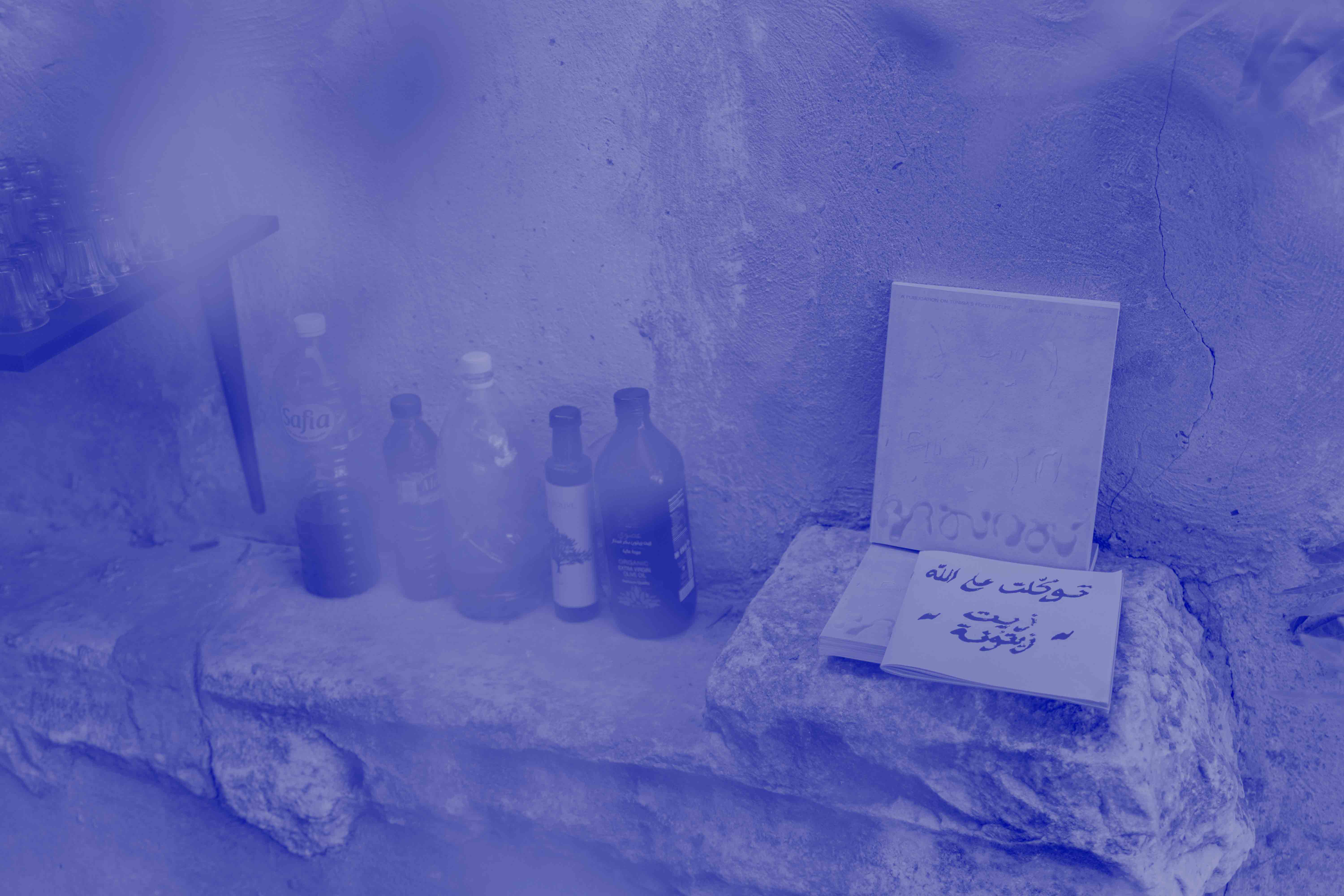

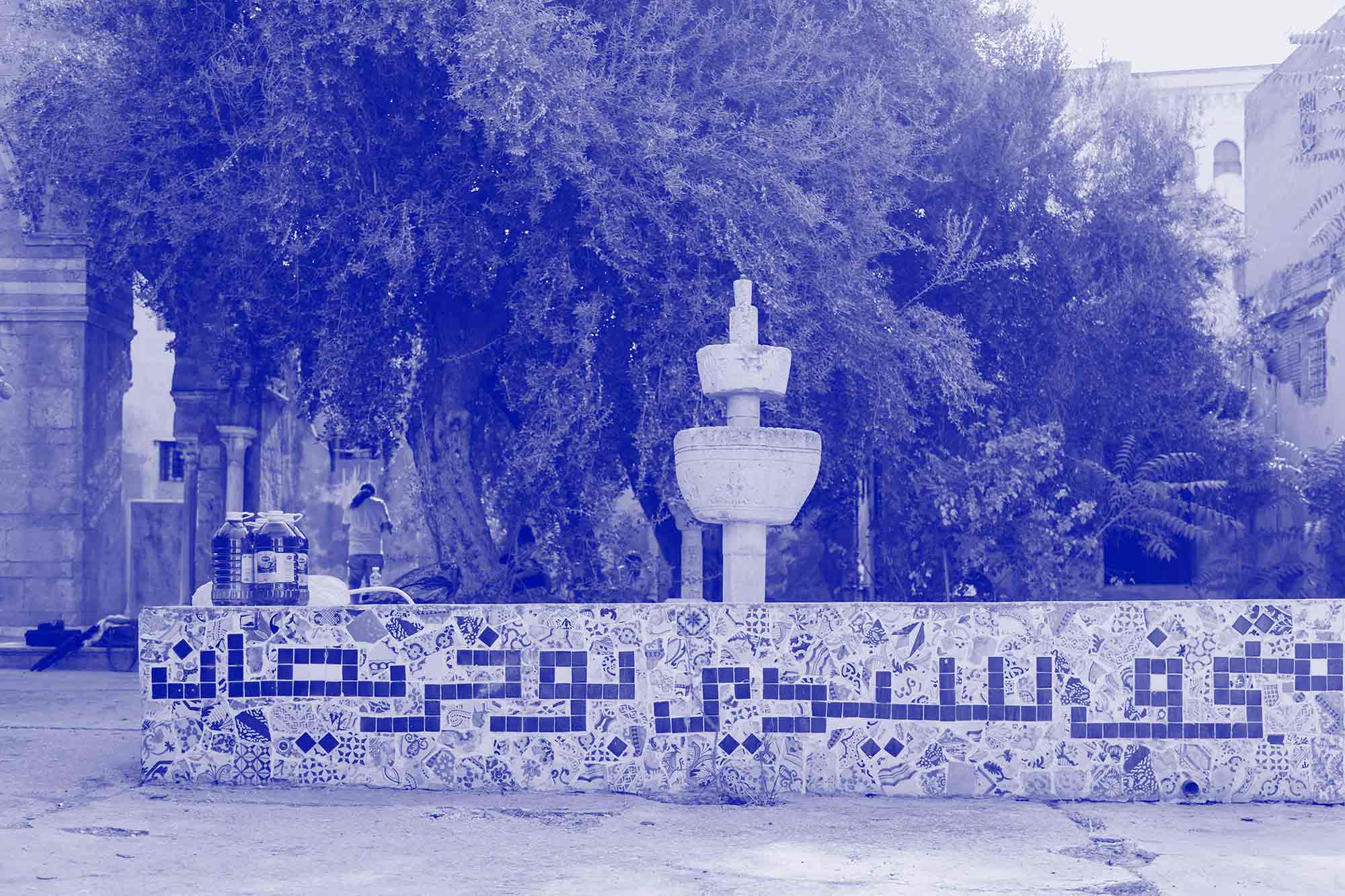

Olive Gathering at Dream City 2023 © © Malek Abderrahman.

Olive Gathering at Dream City 2023 © © Malek Abderrahman. The Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind (PMNHH)–this artwork-cum-institution that has evolved over twenty-five years–may indeed be considered the very first post-Oslo Palestinian museum. This quality of both real-and-imaginary pertains to the museum’s objects and techniques, as well as the project’s many iterations and instantiations, which over time and in their cumulative effects have produced it as an expanding, plastic assemblage. This assemblage is a recurring gathering of people and things, bodies and institutions: the audiences, the producers of the exhibitions, the gallerists; but also the galleries, spaces, museums and biennials hosting the PMNHH, along with the material configurations and the multiple devices and technologies that over the years have made the project possible, real. The museum’s collections include "natural artifacts." For example, in the Geology and Palaeontology Department, there are fossils and meteorites that are made of wood from the olive tree, a key symbol of Palestine and Palestinian nationalism. There are also all kinds of matter in transformation, including copies of copies of icons, such as Sliman Mansour’s Jamal Al Mahamel from 1973. This work remains key to a Palestinian art history that Rabah reproduces through a painting of a photograph of the original painting and a hyperrealist sculpture also copied from a reproduction.

It is the project’s recursive practice of re-enacting and restaging the museum that has given this assemblage a discrete institutional stability and a unitary semblance. The reality of this ‘museum’ is an effect: scattered across varied iterations, it unfolds through these many successive performances. It is the PMNHH’s paced mocking of standard museum routines and devices that gives it such unity and stability: the fact that this museum possesses display cabinets of various kinds and, at times, a building, itself – even if in different locations (often not in Palestine) – and that it produces regular newsletters, all make this both a real museum and a trenchant critique of its material realities.

The PMNHH mocks the traditional form of the so-called ‘universal museum’, that vast collection ranging from natural history to archaeology to ethnography that constituted the core of the first national museums in Europe’s metropolitan centres (often built on colonial plunder) in the nineteenth century. The PMNHH’s second major iteration – its very first independent building – was installed in 2006 in the shadow of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens, which it resembled in (miniaturised) form. It thus absorbed legitimacy, so to speak, from what is a polysemic icon; that is, a key symbol of European heritage and of a recent wave of monumental, nation-branding museums by ‘starchitects’ proliferating across the globe. The Acropolis Museum is also a key symbol of claims for the restitution of stolen cultural heritage (the Parthenon marbles) by (post)colonial nations (or cryptocolonial in the case of Greece; see Herzfeld 2002).2 Undoubtedly, this specific location for this instantiation of the PMNHH evokes the loss and spoliation that is at the core of (post)colonial cultural heritage and nation-state building. Yet, this project is not simply one of critical representation – of mimesis – but also of poiesis, in the ancient Greek sense of creating and making.3 Whilst through parody it deconstructs the museum form, it also proposes and promises one, offering a prototype of a Palestinian museum to come. But if iteration produces a semblance of durable infrastructure, the PMNHH’s iterations-with-a-twist also destabilise and sabotage the standard museum form.

[...]

It is arguably the trick of anticipatory representation that produces the ‘reality’ or ‘becoming real’ of the PMNHH and the RB [Riwaq Biennale]. This is similar to what Donald Preziosi calls the mythological, ‘uncanny space-time of museology’: museums manufacture belief in the prior existence and independent agency of what their objects are taken to represent, often the spirit of a nation. Past, present and future further stand connected in a ‘relation of incompletion and fulfilment’ as the past prefigures and necessitates the present and the future. A display of the permanent collection of the PMNHH, called Palestine before Palestine, has been on view at several of the museum’s iterations. The preposition ‘before’ points to Preziosi’s uncanny space-time, or what I would call a ‘temporality of the promise’ that Rabah overamplifies and distorts. Palestine before Palestine necessitates or precipitates that which it represents, as it announces that there is a museum with an established collection. That museum must therefore be ‘real’. By giving (seed) form to a museum collection, or to a cultural management infrastructure, as in the case of RB, Rabah produces a sense of anticipated coming, of necessary future fulfilment, as well as an infrastructure. The PMNHH and the RB play with the common-sense notion that a representation cannot come before its referent; through these projects, we are drawn to believe, sensuously, that the referent is there, or at least on the verge of coming. Not simply a critical representation of the museum, archive and biennial institution, the PMNHH and the RB are anticipatory institutions in flux.

References :

1. Foster, Hal. ‘An Archival Impulse’. October Vol. 110 (2004): 3–22.

2. De Cesari, Chiara. ‘Anticipatory Representation: Building the Palestinian Nation(-State) through Artistic Performance’. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 12/1 (2012): 82–100.

3. Herzfeld, Michael. ‘The Absent Presence: Discourses of Crypto-Colonialism’. The South Atlantic Quarterly 101/4 (2002): 899–926.

Share

Read more

-

prayer for Palestineadrienne maree brown

-

Becoming Stateless, Overnight!Iyad Alasttal

-

Haj Kanaan Shaina: A Voice from Ein QinyaTareq Khalef & Haifa Zalatimo

-

Looking for AïdaJalila Baccar

-

Cynicism and Western Lack of Insight Pave the Way for the AbyssSophie Bessis

-

Where Nature Ends and Settlements BeginJumana Manna