The Mirage of Exporting Tunisian Sun

Aïda Delpuech & Arianna Poletti

Original text in French – English translation by Yasmine Perkins

Originally published with our partner organization Inkyfada, a Tunisian independent media outlet; recently expanded and re-released through Le Monde Diplomatique.

Importing the Saharan sun to secure a clean, low-cost energy supply has been the dream of European countries and certain stakeholders in the private energy sector since the 19th century. Today, this utopia is on the verge of becoming a reality. In Tunisia, a giant solar power plant developed by the TuNur company could be constructed in the next few years, with the ambition of supplying low-cost electricity to two million homes on the "Old (European) Continent." Apart from being reminiscent of the colonial extractivism we once thought was a thing of the past, this project will not come without consequences for the local population and resources.

In the Tunisian Sahara, on the road leading to Rjim Maatoug, along the border with Algeria. Under military administration since the 1980s, this moon-like landscape of palm groves could soon be trading in its black gold for the promise of green energy. It is here, far from the public eye and on collective lands that were once home to nomadic populations, that the Tunisian-British company TuNur has set its sights on constructing one of the world's largest thermodynamic solar power plant projects.

"Solar and wind energy are infinite, and Tunisia has an abundance of both," says the company, whose ambition is to produce 4.5 GWh of electricity to be exported to Italy, France and Malta. Described as unrealistic by some analysts, this titanic project could very well benefit from the current energy crisis. With the outbreak of the war in Ukraine more than two years ago, European energy markets have had to radically restructure, making the southern Mediterranean - as close as it is rich in natural resources - a very appealing prospect.

Countries such as Morocco, Egypt and Saudi Arabia are all vying for the title of the ‘new energy hub,’ and while the crisis has made North Africa a highly sought-after source of supply, as is the case for Algeria, it's not solely for natural gas. At a time when the price of a barrel of oil remains high and supply challenges are mounting, Europe is pragmatically seeking to accelerate the transition to the less costly options of renewable energies. However, the European continent does not intend to source all its green energy needs from its own territory, and is therefore now coveting the rays pouring in from its southern Mediterranean neighbors, a region with one of the highest solar potentials in the world.

"Africa will certainly be the most important partner for Europe in the development of renewable energies", Frans Timmermans, the European Commissioner for Climate Action at the time, said at a conference organized by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) in Abu Dhabi in January 2023. This statement echoed the commitments made within the Green Pact for Europe which was signed at the end of 2019. A few months later, at COP28 in Dubai, the Vice-President of the European Commission, Maroš Šefčovič, announced an investment of over 20 billion euros for the Africa-EU Green Energy Initiative (AEGEI).

In Tunisia, these ambitious plans are starting to take shape. On July 16, 2023, the country signed a memorandum of understanding with the European Union for a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’. In addition to immigration control, the main themes of the agreement include investment in renewable energies: "The aim is to improve security of supply and provide our people and businesses with clean energy at affordable prices," said European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Of course, the commission's aim is to reassure its southern partners. According to her, it will also be a matter of "creating good jobs locally" in a "win-win situation" which is in "everyone's interest". However, the agreement makes explicit reference to an initiative that will likely mainly benefit Europe. More specifically, this refers to the Elmed project, a 600 MW underwater cable that will link the Tunisian and Italian power grids — a prototype that Rome would also like to duplicate with Libya.

However, these mega-projects will not be without impact on local populations and resources. At a time when only 3% of Tunisia's electricity is generated from renewable energies - a far cry from official ambitions to reach 35% by 2030 - and the country, embroiled in a financial crisis, is struggling to meet its climate targets, many foreign investors are coveting Tunisia's solar resources, albeit mainly for export to the global north. This pattern is reminiscent of the process of exploiting fossil fuels.

Road from Nafta to Rjim Maatoug

The Mediterranean, a one-way energy bridge?

In the name of exporting "clean" energy from the south to the north, plans to build underwater power cables between the two shores of the Mediterranean have multiplied in recent years. In Morocco, the British company Xlinks has announced the construction of the world's longest maritime cable network - 3,800 km by 2029 - as well as the installation of a 10.5 GWh solar power plant to supply electricity to 7 million British homes, i.e. 8% of the country's electricity needs. Egypt has also begun work on a maritime electricity link with Cyprus and Greece, and Algeria has also announced plans to supply Italy and parts of Europe with clean energy via a new underwater cable.

However, so far, only one such initiative has gone beyond the announcement stage: the Elmed project, which links the towns of Kélibia (Cap Bon, Tunisia) and Partanna (Sicily, Italy) and is soon to interconnect the Italian and Tunisian power grids. A "godsend" and "project of the century", according to the enthusiastic Tunisian press, the forthcoming project will give rise to "a new energy corridor between Africa and Europe, promoting the security of energy supply and increased trade in energy from renewable sources," according to Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

In November, following the approval of an initial installment of US$ 268 million in financing by the World Bank in June 2023, Terna, the company managing the Italian electricity transmission network, and STEG, the Tunisian electricity and gas company, signed an additional financial agreement for 307 million euros, paving the way for work to begin. “For the first time, funds from the European Union’s ‘Connecting Europe Facility’—which supports the development of key projects aimed at modernizing Europe’s energy infrastructure—have been allocated to a project between a member state and a non-member state,” noted European Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson during the PCI (Projects of Common Interest) Energy Days. While the interconnection project with Italy is rapidly progressing, there is still a shortage of both solar and wind power plants to supply the national grid, which is largely dependent on Algerian gas. For the time being, however, the influx of foreign currency through the export of renewable energies seems to be taking precedence over the imperatives of energy security and self-sufficiency. Unlike its Algerian and Libyan neighbors, Tunisia cannot rely on hydrocarbon revenues and is betting on renewable energy exports to put it at the forefront of the energy transition.

The semi-desert zone of Shatt El Jerid

The semi-desert zone of Shatt El Jerid

Export lobbying

Behind TuNur's ambition to build the world's largest solar power plant lie the interests of a handful of well-known investors from the London financial world, keeping a close eye on the promising future of green finance. At the helm of the company is British investment banker Kevin Sara, founder of several investment funds in the United Kingdom, and the managing director of the solar energy developer Nur Energie, the company that owns TuNur ltd alongside the Maltese Zammit group.

If TuNur has made any progress in recent years, it was mainly in the business of lobbying, both in Tunis and in Brussels. Established in Tunisia in 2012, it has made major contributions to the creation of a favorable legislative environment for renewable energy exports to Europe. Since 2020, the company has been listed in the EU Transparency Register, a database of organizations seeking to influence the legislative and policy-making processes of European institutions.

The company seems to show particular interest in the European Green Deal and the European Network of Transmission System Operators, an association representing about 40 electricity transmission operators. "We need the Tunisian State to work with us in order to develop a roadmap with European countries to ensure that Tunisian clean energy can compete on the market," explained consultant Ali Kanzari, TuNur's top advisor in Tunisia and President of the Tunisian Photovoltaic Union Chamber (CSPT). He confirms that the company is already actively approaching electricity distribution companies in Italy and France.

TuNur is one of the projects that have been shortlisted in the joint European Ten-Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP) for 2022, a necessary step to join the ranks of the EU's Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) in the interconnection of European energy networks. Once selected, applications are eligible for simplified regulations and financial support from Brussels.

On the other side of the Mediterranean, the company has worked tirelessly with Tunisian institutions to form "a powerful lobby to obtain the inclusion of export provisions in the renewable energies legislation," as stated in the latest energy report by the Tunisian Observatory of Economy (OTE). This was achieved by ratifying access to electricity generation and distribution for private companies, which previously had remained a monopoly of STEG, a heavily indebted state-owned company.

Approved in 2015 and amended in 2019, Law No. 2015-12 on renewable energy paved the way for the liberalization of the Tunisian electricity market, despite fierce opposition from trade unions. As a result, all renewable energy projects approved by the Ministry of Energy remained blocked until the end of 2022, due to the refusal of STEG trade unionists to connect the country's first private photovoltaic plant to the electricity grid.

Located in Tataouine, in southern Tunisia, this infrastructure is managed by Eni - the multinational Italian oil and gas company - in partnership with the Tunisian Oil Company (ETAP), and is co-financed by the French Development Agency (AFD). "We are urging the State to revisit this law that was ratified under pressure from multinationals. We're not against renewable energies, we're simply demanding that they be made available to Tunisians, electricity must remain a public property," says Ramzi Khlifi, a trade unionist who took part in the blockade.

Against this backdrop of tension between STEG, Tunisian institutions, and private companies, TuNur still managed to carve out a place for itself on the local market through the construction of a small photovoltaic solar power plant in Gabès in 2019. In August 2022, the company announced an initial investment of 1.5 billion euros for its main project.

In Mr. Kanzari's office in Tunis, an old map of the Mediterranean streaked with multicolored cables illustrates the very first version of the project. "[Tunisia's] trade with Europe is strategic, and must not be limited to dates and olive oil. Tunisia is capable of meeting Europe's growing need for green energy. It's a question of political will."

TuNur did not wait for tenders from the Ministry of Energy for an export concession, which is a must for any renewable energy project in Tunisia. Before any impact study was conducted on water resources, the company had already "signed a pre-lease agreement for a 45,000-hectare plot of land located between the towns of Rjim Maatoug and El Faouar with the El Ghrib Collective Land Management Council, which owns the site," recounts Mr. Kanzari. The solar power plant would cover 25,000 hectares, almost three times the size of Manhattan — an unprecedented undertaking.

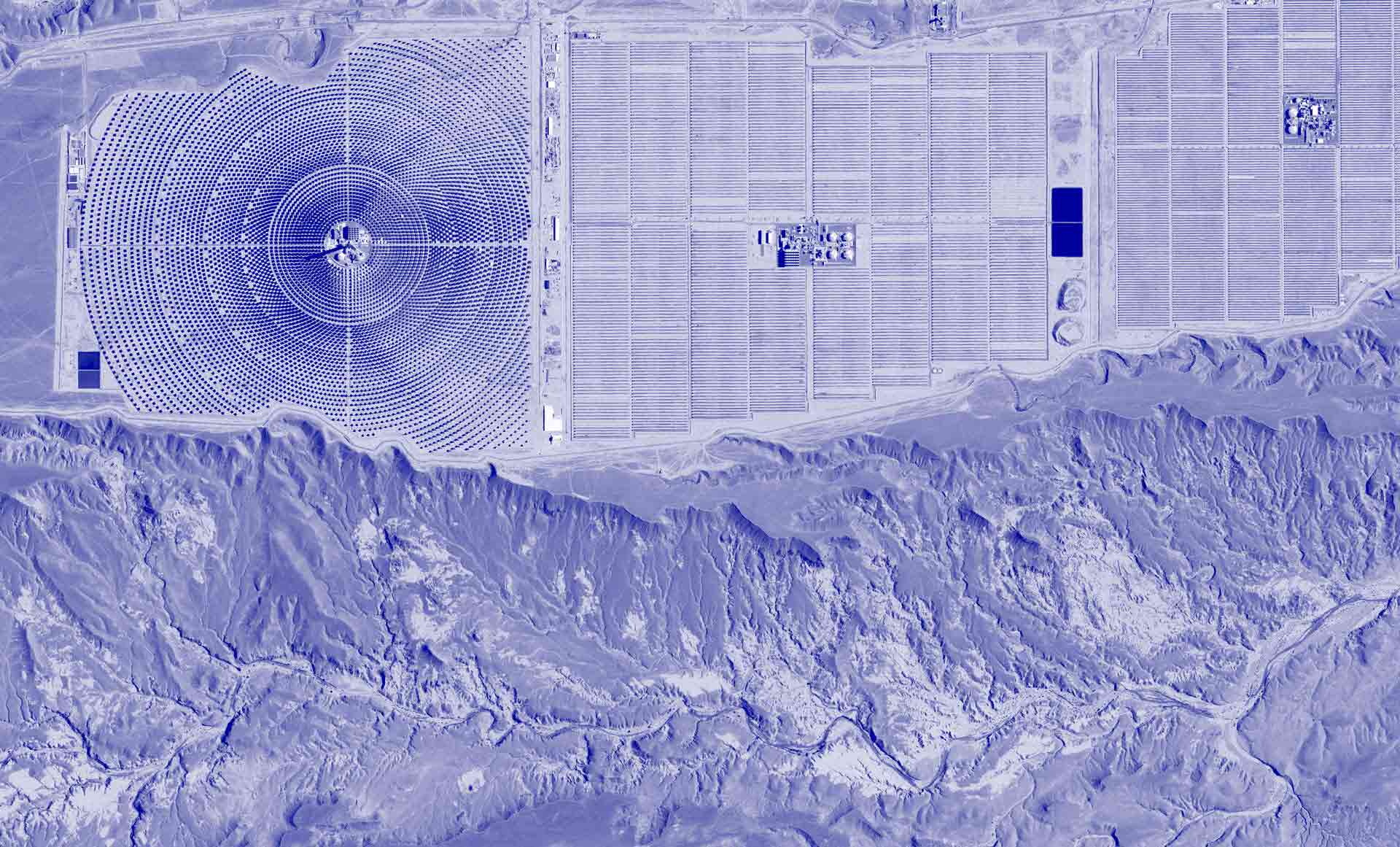

Aerial view of the Noor solar power plant in Ouarzazate. Photo credit: Federico Monica, Placemarks Africa

Aerial view of the Noor solar power plant in Ouarzazate. Photo credit: Federico Monica, Placemarks Africa

A project copy pasted from a Moroccan template

Tunisia is not the first North African country to be coveted for its ‘solar potential’. TuNur is in fact inspired by a Moroccan mega solar power plant called Noor (“light” in Arabic), located in the south-eastern Moroccan desert, a few kilometers from Ouarzazate. In a rocky, irregular landscape that is often covered in ochre dust, hundreds of luminous strips impose their geometric order across 3,000 hectares. On a clear day, the central tower towering above the reflective mirrors is even visible from the city.

Officially inaugurated in February 2016 by King Mohammed VI himself, Noor - the world's largest thermodynamic power plant to date - has become the hallmark of a national policy geared toward the expansion of renewable energy. The Cherifian kingdom boasts a renewable energy share of 37% in its overall energy balance, well ahead of many European countries.

"The Moroccan politics of expanding renewable energies originated in a context similar to that of today: the surge in oil prices that preceded the financial crisis of 2008," observes Jamal Saddoq, a member of the Attac Maroc association in Ouarzazate, and one of the few figures to challenge extractivist policies in the kingdom. Since then, Morocco has embarked on a frantic race towards renewable energy, with the ultimate goal being to export this new green gold.

The gigantic Ouarzazate project, managed by the Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (Masen) and the Saudi group ACWA Power and widely celebrated by the media, is now the target of much criticism. According to a 2020 report by the Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE), an independent consultative institution, the very high energy prices imposed by the Saudi company on the Moroccan government are digging a yearly hole of 800 million dirhams (nearly 74 million euros) in public funds. Meanwhile, the Masen agency is under investigation for mismanagement of funds.

A dry oasis in the Draa Valley, east of Ouarzazate

A dry oasis in the Draa Valley, east of Ouarzazate

In addition to the economic losses it generates, the plant is also accused of employing water-intensive technology in a region already suffering from structural water shortage and where protests have taken place continuously since 2017. Inhabitants denounce the monopolization of water resources by large-scale agricultural, mining and energy projects supported by the state. "The Noor power plant is one of them," Mr. Saddoq states. Echoing the views of the region's farmers, he is quick to denounce the project as "extractivist and imposed from above". He also asserts that, despite the many promises, the southeastern communities of Morocco "have not benefited in any way".

On the contrary, water resources have been steadily dwindling, to the dismay of farmers and residents alike. The lake in the El Mansour Eddahbi dam, which irrigates the entire Drâa valley, is used by the solar power plant to cool down the mirrors that maintain them in the desert environment. Currently operating at 12% of its total capacity, it is the region's main water source for both drinking and irrigation. Farmers paint an alarming picture: "Our valley is on the verge of collapse, as all our water is directed to the dam to meet the needs of the solar power plant," complains Youssef N., a farmer from Souk El-Khamis, a village in the Dades valley. In this area renowned for its rose cultivation, each village is named after the wadi (river) that runs through it. Today, bridges overhang dry wadis full of nothing but pebbles.

The environmental impact study carried out prior to the construction of the solar project predicted an annual consumption of six million cubic metres of water. "It's impossible, however, to get official statistics on the actual consumption," notes researcher Karen Rignall, an anthropologist at the University of Kentucky and a specialist in rural energy transition. "An official at the Office for Agricultural Development in Ouarzazate, which is in charge of managing this dam, anonymously admitted to us that the Noor complex did not inform them of its water withdrawals. The actual consumption seems to be considerably higher," she added.

However, the plant that TuNur is planning to install in the heart of the Tunisian desert, in the Kébili region, is as much as nine times larger. Just like in Morocco, the local oasis system is equally damaged by drought and the effects of global warming. According to the Nakhla association, which works with farmers in Kebili, the region is already overexploiting its resources. The ecological setbacks of the Moroccan power plant are just a glimpse into the potential impact of the TuNur project on the already fragile ecosystem of southern Tunisia.

Installation of a water pump in Fawwar

Importing the sun, a colonial utopia

Harnessing the sun's rays in the Sahara has been a long-standing ambition as old as colonization itself. Initially viewed as unproductive and inhospitable, the world's largest desert gradually piqued interest as industrialization swept through the Old Continent. Paul Bouet, a postdoctoral researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and an authority on the domestication of solar energy, notes, "The intention was to integrate this seemingly barren expanse into the economic growth and industrialization efforts of colonial powers."

In the context of Tunisia, Aymen Amayed, a researcher specializing in agricultural policy, explains that "the colonial authority sought to quell resistance from southern tribes by seizing their land". During the early years of the Third French Republic, the notion of the 'conquest of the sun' was championed through official propaganda as a symbol of modernity. The concept of harnessing solar power continued to captivate minds, being portrayed as a breakthrough capable of liberating humanity from its limitations. In the latter half of the 19th century, Augustin Mouchot, a prolific engineer, developed a series of steam engines utilizing concentrated solar energy technology. Mouchot was among the first to recognize the potential of North African sunlight in bolstering industrial growth across Europe.

"In these regions, the sky remains consistently clear for months, allowing for the collection of sunrays for ten to twelve hours each day, and what rays they are!" he exclaimed in his writings. In 1877, Mouchot secured public funding to conduct experiments in the Algerian desert with the support of military personnel and industrialists. “The objective was clear: to harness the Sahara's solar potential to cater to the needs of European empires,” Bouet continues. For the French government, this endeavour promised dual advantages: fostering national pride through industrial progress and asserting dominance in African colonies, while simultaneously exploiting their resources for the benefit of the metropolis.

Despite initial enthusiasm, interest in Augustin Mouchot's solar vision diminished rapidly, as it struggled to compete with coal, Europe's primary energy source at the time. Consequently, Mouchot was compelled to halt his research efforts. Nonetheless, the concept of harnessing solar power endured and continued to resurface throughout the 20th century, eventually evolving into the prominent priority it is today. In 2009, against the backdrop of mounting concerns over fossil fuel dependency, the Desertec initiative reignited discourse around tapping into the sun's radiance in the Sahara within European circles. Supported by the German branch of the Club of Rome, an international think tank, as well as the TREC (Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation) network comprising Mediterranean experts, the project garnered backing from a consortium of notable German companies (Deutsche Bank, EON, Siemens, etc.), alongside institutional support from the World Bank and AFD (French Development Agency). This ambitious venture envisioned establishing a network of solar thermal power facilities across North Africa and the Near East.

The goal was to interconnect these plants with Europe via high-voltage trans-Mediterranean power lines, with the aim of meeting over 15% of the continent's electricity demand by 2050. Proponents envisioned this as a means for European economies to expand ‘in equilibrium with the environment’, heralding it as ‘the greatest idea of the century.’

Meanwhile, researchers continued to emphasize the boundless potential of solar radiation in the Sahara. "An area measuring 254 km by 254 km was deemed sufficient to fulfil the global electricity requirements," asserted Nadine May, a researcher affiliated with the Technical University of Braunschweig, in her dissertation. However, internal discord and financial shortcomings led to scrapping the Desertec project in 2012. Despite this, the aspiration to anchor Europe's energy transition in North African solar power perseveres, illustrating the niche that TuNur now seeks to invest in.

Tanour's pre-rented site at Regim Maatouk

Tanour's pre-rented site at Regim MaatoukCapitalizing on the Desert by Any Means Necessary

After Tunisian independence, the rhetoric of the ‘unproductive desert’ was adopted by President Habib Bourguiba, who subscribed to a utilitarian vision of the desert expanses. "In reality, these lands were very fruitful for the local populations, whose primary activity was grazing," Mr. Amayed asserts. What ensued was a vast campaign of land dispossession, which is still at play today.

State-owned land reserves were subsequently sold off as a result of pressure from international financial institutions, most often to large private export-oriented companies. In June 2022, as part of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) - which are still ongoing - the Ministry of Agriculture decided to remove the ceiling on foreign participation in agricultural enterprises (previously set at 66%), thus giving foreign-owned companies the opportunity to own Tunisian land. The proclaimed purpose of such a concession was to ‘stimulate investment’. Two months later, in October 2022, a decree-law (no. 2022-65) gave any public entity the possibility of getting its hands on land of any kind and thereby dispossessing its owner in order to carry out a project of ‘public benefit’.

"The state has created abandoned areas, set aside for potential future capital-intensive projects that are economically more profitable. Today, renewable energies are filling this void," Mr. Amayed continues. With a commitment to revitalizing so-called marginalized regions in the name of sustainable development, TuNur assures that more than 20,000 direct and indirect jobs will be created in the Kébili region, where the number of people aspiring to migrate to Europe continues to grow. A promise not unlike those made by the multinational companies exploiting the hydrocarbon deposits nearby, in the area of Tataouine. Unable to see any employment development in their region, the unemployed youth of the El-Kamour movement have been blocking pipelines since 2017.

In the case of megaprojects, "the majority of jobs are not sustainable, most of them being needed only for the construction and start-up phase of the projects," warns a recent report by the Tunisian Observatory of Economy. The same sentiment prevailed in colonial times, when industrialization was supposed to benefit the local population by improving their standard of living and the colonizer by transporting wealth to the metropolis.

By their very nature, ambitious projects require substantial financing from the outset. However, "most of the public players in the southern Mediterranean are in debt and don't have this type of capital. So it is the private players who are taking over, ensuring that the benefits go to the private sector, while the costs are paid by the public sector," explains Benjamin Schütze, a political science researcher and specialist in renewable energies.

The "extractivist" dimension of these projects is also subject to considerable criticism. This term is typically used to describe processes for exploiting material resources from the ground (metals, hydrocarbons...) that have a high impact on local communities and the environment, while benefiting only wealthy countries - a notion that now also applies to the harnessing and exporting of solar energy.

According to Benjamin Schütze, these megaprojects, which require centralized production, are also easier to implement in authoritarian contexts, where opponents have very little room to maneuver, as is currently the case in Tunisia. The energy transition thus becomes an opportunity to reflect on the link between extractivism and authoritarianism: "This transition should go hand in hand with the adoption of more democratic, decentralized power structures," the researcher argues. "Wanting a rapid transition while ignoring governance structures is dangerous."

Share

Read more

-

Visual Notes of a Fieldwork Research / Cluster of MatterBochra Taboubi

-

Tunis your...Milène Tournier

-

A dialogue with Sebkhet Sejoumi by Natural Contract LabMaria Lucia Cruz Correia & Margarida Mendes

-

Letter from Sebkhet SejoumiCyrine Ghrissi

-

Mohamed Ali Eltaher: When the Tunisian Destiny Met with the Palestinian CauseAdnen el Ghali

-

STIGMAJalila Baccar